Stay on Top of Important Discoveries

We read case studies and academic journals so you don’t have to. Sign up and we’ll send you the key takeaways.

Why do so many school districts opt for performing teacher observations? Observations “give teachers the opportunity to receive meaningful and direct feedback about their practice.” Teachers need a mechanism for feedback to affirm how effectively they convey concepts, decipher what areas could be further enhanced, and instill a mindset of continuous improvement. Highly accurate observations and metrics are imperative, as teachers’ objective “ratings” in most districts are determined by the majority of their given classroom observations.

However, getting started with a teacher observation process, or revamping a current process, is a stressful endeavor, especially when considering all that is expected of these observations. Simply put, too much responsibility is placed on observers themselves. Though technology surely has advanced to more than solve the issues observers face, many struggle to make precise observations of the skills that are displayed in the classroom, and therefore fail to adequately aid the teachers that rely on them. Of course, this is not the fault of the observer! Many common rubrics are too lengthy or lack specificity. Others expect data on more actions than one viewer could possibly detect simultaneously. Essentially, observers are trying to assess too many things at once.

In other cases, the struggle of teacher observations starts at the source or is a systemic issue. Observers aren’t given the time to improve their observation skills before they’re thrown into the undertaking. Teachers themselves might be unclear about the expectations for teacher practice. Principals might be unable to find the time to give feedback to teachers after observations have taken place.

There are methods to combat these underlying issues. Nonetheless, it is clear that the most effective place to start is by implementing high-quality observation instruments. No, this doesn’t mean ordering in some sort of complicated, physical equipment or mechanisms to put these struggles to rest. It does include, however, a two-part process: developing a quality rubric and harnessing the power of a video platform for education for easy implementation of that rubric.

Developing A Quality Rubric

A streamlined rubric is always most effective. In fact, many research studies on classroom observations inform educators that rubrics are most effectual when they display signs of…

- Coherency: Is this rubric aligned with state or district teaching standards?

- Conciseness: Does this rubric attempt to collect the most useful information possible with the least number of separate observations possible?

- Clearness: Does this rubric employ precise language?

- Focus: Do the indicators this rubric seeks relate directly to real student outcomes?

While these four qualifications are helpful in getting started with effective rubrics, they themselves are not specific enough. To meet these four prerequisites of a quality rubric, (coherency, conciseness, clearness, and focus), there are five further underlying qualifications that meet the need for specificity while directly correlating to the standards for highly-effective rubrics.

Five Qualifications for Creating a Clear, Streamlined Rubric

Observable

This first qualification is important for everyone’s sanity. We can’t continue to expect observers to observe what is unobservable. An observer cannot be held accountable for reading a teacher’s thoughts, drawing implications with minimal information, or imagining a teacher’s purpose for a certain instruction. Instead, observers should be responsible for tracking behaviors. Within this first qualification, “Observable”, there are two facets. Firstly, “observable” relates to the action taking place externally, rather than internally. For example,

“Teacher addresses misunderstandings”

is an external behavior that can be documented, while

“Teacher uses strategy to convey concepts to students”

is not. Secondly, “observable” relates to whether the action can be reasonably detected across a given time-span. If a behavior happens across multiple class periods, it is best left off of a quality rubric. For example,

“Teacher poses complex questions to students”

is a behavior that can be recognized in one sitting, while

“Teacher modifies approach to a particular lesson in response to data”

is not.

Student-Centered

This second qualification is targeted at making sure both teachers and observers don’t lose sight of the most important goal of instruction: student education. Because of the importance of staying focused on student outcomes, rubrics should not be only focused on teacher behaviors. Instead, rubrics should be sure to include student-centered detectable behaviors. In the pivot to hone in on student learning instead of teacher teaching, observers can ask themselves such questions as “What do we want students to learn?” and “How do we know students are learning?” For example,

“X number of student hands are up in the classroom when reviewing previously taught material”

is a behavior focused on student outcomes, while

“Teacher periodically emphasizes completion of work and encouragement to turn in quality work to students”

is only teacher-focused. Another meaningful and measurable way to stress student learning would be a criterion that evaluates whether students are engaged in a lesson, and when they are not engaged, how much time elapses before a teacher brings them back on task.

Reflects High Expectations

Setting high, challenging expectations for teachers is possibly counter-intuitive, depending on the culture of your school or district, but is precisely one of the best practices that should be incorporated into a quality rubric. In fact, setting high expectations directly builds both resiliency and efficacy (confidence) within teachers, leading to an increase in psychological capital. Settling for minimally acceptable performance only, with no scale to show how improvement may be obtained, cannot be the only standard teachers are faced with. For example,

“Teacher is capable of certifying that every students’ needs are met, and is capable of providing support to struggling students when necessary”

is a high standard for teachers to meet, and therefore challenges them to continually work for improvement, while

“Teacher uses the technology required for the instruction of a given lesson”

is simply compliance-driven, and shows little to no real merit.

Another effective and necessary way to create high expectations is to differentiate between performance levels. If teachers clearly understand what criteria are imperative for reaching the next level, they can constantly be challenged to grow and develop, as goes the old saying “there is always room for improvement”. For example, a rubric might characterize two performance levels in the area of developing students’ high-level thinking skills as “developing” and “proficient”.

Developing

“Teacher uses questioning to develop students’ higher-level thinking skills”

Proficient

“Teacher uses both questioning and a variety of other instructional strategies to develop students’ higher-level thinking skills, which are proven effective by the length of thoughtful answers students give to divergent questions”

Includes a mixture of Divergent and Convergent Questions

A simple but helpful and effective item to add on a rubric, teachers asking a mix of both convergent and divergent questions allows an interesting insight into how a classroom operates. While convergent questions are those that require only a single word or phrase answer and usually require answers that can be immediately qualified as correct or incorrect, divergent questions are those that require more than knowledge on a subject but also thought, interpretation, and thoughtful response. Divergent questions are open-ended and tend to promote discovery and student engagement. Both types of questions are valuable to gauge what students are potentially lacking, and so a healthy mixture is generally best practice. This mixture can be decided based on the current needs of your classrooms.

Does not place emphasis on support materials

For the purpose of teacher observation, rubric items that assess support materials, such as regulatory lesson plans, standards-based guides, and students’ work, should not be included. These criteria would be better assessed using separate resources and time as to not distract observers from the focus at hand: teacher behavior. For example,

“Teacher implements strategies to maximize group work time”

is an example of a criterion that draws on the effectiveness and resources of a specific teacher, while,

“Teacher completes section A, B, and C of Week 7 Iowa 3rd Grade Lesson Plan”

is a criterion based on a specific support material.

Harnessing the Power of Video

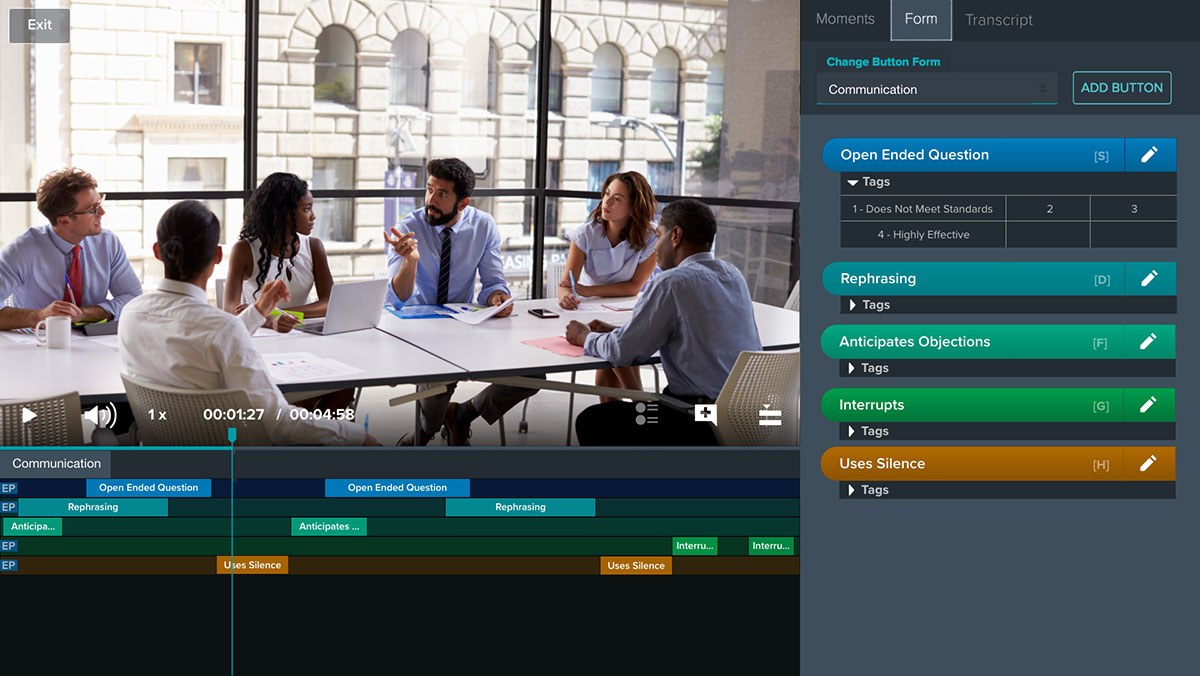

Getting clear and concise on what observers should be attentive to is only helpful if it’s possible to actually see the actions a teacher performs. This is where Vosaic, a video platform for education, comes in. In every classroom, important learning moments go unnoticed. Vosaic helps observers record, identify, and share those moments with easy-to-use video analysis software. Users can create feedback forms based on best-practice frameworks like Danielson’s, or can create their own, using the important qualifications of rubrics, to best suit their specific goals. Important moments can then be marked using the created form as a video is being recorded, or after. Finally, comments can be added to provide feedback, and videos, with the marked moments and comments, can be shared with others for review.

If you don't have a Vosaic account for teacher coaching and observation, you can start with a free trial today.

The clear benefit of using video within observations is the ability to go back and review the video at any point, watching for specific criteria, instead of performing the overwhelming task of trying to observe all the important moments simultaneously, in real-time. However, the benefits reach beyond those that the observer gains. Video ensures that teaching is effective, allows teachers to take part in evidence-based feedback, and places a focus on continuous improvement. It allows for both self-reflection and constructive feedback from peers. This means that colleagues will better know how to support, mentor, and promote instructors when it comes to their teaching effectiveness. The more we engage teachers as learners, the better their classroom practices will become. Matt Rinne, an instructional coach at Prytle Elementary in Lincoln NE, had this to say about Vosaic’s video platform:

“Vosaic allows teachers to focus on what they’d like to improve in their teaching. As an instructional coach it’s really easy for me to create a feedback form that focuses on their goals, and then choose that form to make up their video at the time of their recording.”

Video certifies that no one individual’s opinions hinder progress. Instead, factual data can be harvested and produced as evidence to direct instructors toward improvement. Video also mitigates the busyness of teaching and affords teachers the opportunity to watch their teaching and reflect on practice. When teachers watch themselves teach, they can find evidence to affirm or reject beliefs they have about teaching and learning, therefore eliminating confirmation bias.

“When using Vosaic to review the video later in my office rather than text documentation, I found that my text documentation was filled with biases,” mentioned Kevin Chick, principal at St. Columba in Durango, CO. “I only documented when I saw the things I was looking for. I missed many activities while documenting.”

A Final Note

Beyond powerful rubrics and video utilization, various initiatives can be taken to improve teacher observations. Developing supplemental tools, such as a shorter version of the rubric that contains only the absolutely observable criteria, helps observers focus on the most important areas of development. Furthermore, these matters should be taken to the stakeholders themselves: teachers, observers, chairs, etc. Simply asking for feedback and making a concerted effort to implement that feedback is an effective way to tailor these suggestions to a specific school’s unique needs. After all, the goal is to establish that educators’ needs are being met.